Piggybacking on its main stage production of Puccini’s La Boheme this past January, the Atlanta Opera opened its 2024-2025 season under the banner of its Discovery Series this past Wednesday with The Boheme Project, an alternating double bill of sorts, featuring an updating of Puccini’s classic to modern times, alongside performances of Jonathan Larson’s Rent at Pullman Yards. The idea at play is to present La Boheme “two ways” featuring two different pandemics, COVID-19 for La Boheme and HIV for Rent respectively. Both works share the same stage, alternating calendar dates from mid-September through early October. For the purposes of this review, I limited my attendance to Puccini’s familiar classic, which elicited surprising reactions as presented by the Atlanta Opera’s celebrated experimental project.

Ever since taking the helm of the Atlanta Opera, General and Artistic Director Tomer Zvulun has placed great emphasis in extending the company’s reach deeper into the fabric of the community in ways never attempted by previous administrations. Under his leadership, the Atlanta Opera unveiled the Discovery Series, a longstanding project designed to complement the company’s main stage standard repertoire. Under this branding the Atlanta Opera has been on the move – offering new works (such as the premieres of David Little’s Soldier Songs at the Rialto Center for the Arts and Jake Heggie’s Out of Darkness: Two Remain at The Balzer Theater at Herren’s) to less explored pieces by established masters (a fragrant production of Mozart’s La Finta Gardiniera at the Botanical Gardens, an intimate presentation of Bartok’s Bluebeard’s Castle at Kennesaw State University) often in unconventional settings. The project allowed the Atlanta Opera to gradually expand beyond the standard repertoire in a digestible way, setting itself apart from regional companies afraid to shake the table.

Then COVID-19 happened, halting the company’s production of Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess mid-run in March of 2020, and placing planned productions of Puccini’s Madama Butterfly and Cipulo’s Glory Denied on hold. As the lights dimmed in theaters across the globe, The Atlanta Opera capitalized on the ground gained by its daredevil side project to make lemonade out of rocks, adapting its presentation format into compliance with the age of social distancing. By August of that same year, it unveiled its Big Tent Series, reformatting opera productions in an open field (I was too paranoid to attend in person, but I heard about it,) and earning critical recognition along the way. By fearlessly championing the company’s experimental edge, the Discovery Series helped the Atlanta Opera weather the lockdown measures, enabling a smooth transition back into main stage productions at the Cobb Energy Center with Handel’s Giulio Cesare in November 2021. For its part, the Discovery Series first trial balloon at Pullman Yards took place the following year with the Come As You Are Festival which featured productions of Cabaret and Kaminsky’s chamber opera As One.

First time Pullman Yards attendees will do well to arrive early. GPS service can get dicey as you make your way through the narrow streets surrounding the complex, and early arrivers may be kissed with the elusive on-street parking blessing. Once inside, the format feels quite different to those accustomed to standard classical music venues in Atlanta. Located in the northwest edge of Kirkwood, the historic complex has endured many reincarnations (from bomb manufacturing to luxury rail car maker), and since being refashioned as a giant event space by Atomic Entertainment in 2017, it is now the host of the party. The vibe is, for lack of a better term, “grown hooligan,” with new wave classics (played at reasonable volumes) welcoming ticket goers into the giant exposed brick warehouse. Seating sections have been suggested by cleverly placed curtains, and those seeking to handle pre-performance business will be wowed by the fanciest port-a-potties I have ever seen (they have mirrors!). Younger me would have felt right at home.

Sharing production and set design duties, Tomer Zvulun and Vita Tzykun should be credited for delivering a visceral experience by retrofitting the auditorium’s industrial essence to grace the event, leaving exposed the raw plumbing serving the show. A circular stage-like runway, flanked by a balcony separating the orchestra from the action on one side, and a scantly furnished platform representing the student’s garret at the opposite end. Overhead, heavy scaffolding supports the lighting and sound equipment which feeds the sound stations behind the bleachers. The experience is immersive (at least for those able to land a table in the center of the catwalk,) and depending on the blocking agreed upon by the co-directors, the action may just be facing your side of the room.

It was certainly a lot to take in, and I foolishly allowed my eyes to be seduced by it all instead of investing a casual glance at the evening’s playbill. In retrospect, this was a grave mistake. As act one got underway and the bros uttered their opening lines, the blood left my face: The principals were all aggressively amplified, with the voices filling the space with commanding presence from the speakers located above the scaffolding.

The topic of amplification is controversial amongst opera people, and most accept it in varying degrees. Amplification and sound editing is well tolerated in commercial studio recordings and even radio broadcasts. Most operagoers raised on recordings undergo some adjustment to the varying acoustics of the live theater experience, a journey which can be thought provoking. Those present at last season’s Die Walkure will attest to the immediate effect of experiencing artists like Christine Goerke and Greer Grimsley, voices that did not just cut through Wagner’s heavy orchestra but filled the Cobb Energy Center auditorium, only to be juxtaposed with the amplified cries of the Ride of the Valkyries. To my ear, amplification has the effect of witnessing a gymnastics competition taking place under water. The practice also changes the singer’s art as they’re no longer projecting their presence towards the audience directly, forcing them to barter with a mediary which may expose their art in unintended ways. Dynamics get flatten and the sound is both ever present yet two dimensional, and I find myself surrounded by sounds I wish I could hear, you know, for real.

I have always argued that opera in the theater is the true organic, alien, superhuman, simple yet oversized, extreme experience that people instinctively hunger for, particularly nowadays when everything that once made life bearable is either filtered or replaced by plastic. I recall an incident at a Rufus Wainwright concert at the Tabernacle where, midway through his set, Mr. Wainwright stated that he “had to do the old theater justice,” stepped away from his microphone and sang the Irish song “Macushla” acapella. Afterwards, my crew seemed obsessed with discussing the unbelievable event they had just witnessed: The singer sang, and we heard his true voice.

With these questions torturing me during the first two acts of La Boheme, I consulted the evening’s playbill during intermission and was relieved to find an open discussion on the subject located in the Director’s Notes. To accommodate Pullman Yards unflattering acoustics, the decision was made to do away with them altogether. Though I profoundly disagree with this decision, the disclaimer allowed me to reframe the performance within a different context and enjoy it on its own terms.

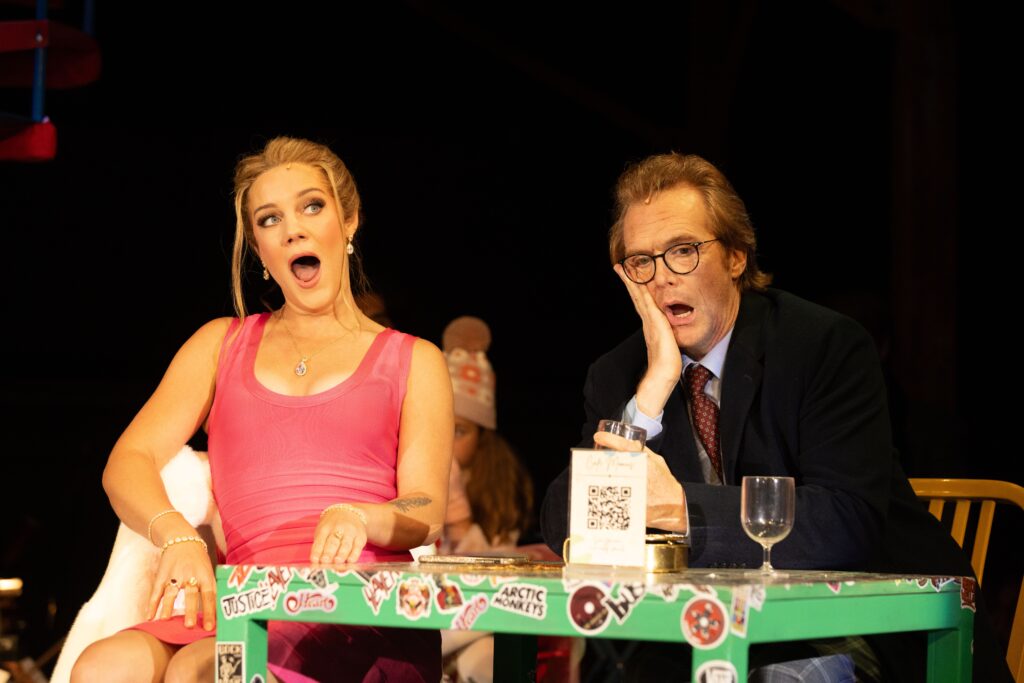

Assessing the show as a musical experience has been tricky business. Leading the orchestra in both La Boheme and Rent, conductor James Lowe is clearly adept at a variety of styles. In La Boheme, he kept the evening organized despite his being sequestered behind the Café Momus for the entire evening. A big part of the conducting gig involves striking the right balance between principals and the orchestra, but under the current conditions an attempt to assess these merits would be decidedly unfair. His principals are comprised of young artists, many becoming familiar faces to Atlanta Opera audiences. As Rodolfo we get Kameron Lopreore, the hunky tenor who first came into this blog’s radar in an uneven performance of Riccardo Fenimoore in Odyssey Opera’s Pacini’s Maria, Regina d’Inghilterra back in 2019. Subsequent hearings in less ambitious parts (Fenimoore was a Nicola Ivanoff vehicle) have revealed improvement in Mr. Lopreore’s confidence and overall technique, culminating in a charming rendition as Lysander in Britten’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream earlier in March. Musically, Mr. Lopreore accomplished the barebones of Rodolfo well enough, though the microphone amplified breaks he has been working hard to smooth over in his scale. These were cleverly weaved by Mr. Lopreore to secure an effective portrayal, yet we will only know the true merits of his Rodolfo when he gets the chance to unveil him in a more appropriate format. His Mimi is Amanda Batista, a young soprano making her debut with the Atlanta Opera with these performances, and she may have been a revelation under normal conditions. In its amplified state, the voice exudes a warm sound coupled with a dome-shaped phrasing so flattering to Puccini heroines, deserving its chance to travel into an auditorium and be admired in its full splendor – I hope she gets the chance. Luke Sutliff’s contribution as Marcello, his second for the Atlanta Opera since his debut as Demetrius in Britten’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream added to his growing reputation as an intense and technically accomplished baritone. He shared a “complicated” relationship status with the Musetta of soprano Cadie J. Bryan, whose high sitting, light soprano was best served by the artificial conditions in the venue.

While the decision to update the action of Puccini’s La Boheme to the height of the COVID-19 crisis is essentially unnecessary for the opera to deliver its emotional punch, there are benefits to portraying poverty in terms relevant to today. Belle Epoque Parisian poverty can strike modern audiences as artificially charming and kitschy, so Mimi collapsing on an inflatable sofa and dropping a solo cup with her last breath made the realism more vivid and ruthlessly relatable. The update also allowed plenty of opportunities for Costume Designer Amy Sutton to style the cast in what stroke me as “their uncle’s hand me downs,” with the spectacular striped southwestern cardigan worn by Rodolfo in the first act deserving special mention. Now, that’s art.

The Atlanta Opera’s Discovery Series presentation of Puccini’s La Boheme and Larson’s Rent run through October 6. By design, these productions aim to explore new ways of presenting opera with an implied note of whimsy and levity. The aim is not perfection, but possibility. For more information on the Discovery Series, or the rest of the Atlanta Opera’s 2024-25 season, please visit the company’s website at https://www.atlantaopera.org/

-Daniel Vasquez