With the ethereal afterglow of Britten’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream still lingering in the air, Atlanta opera goers prepared for the operatic event of the past…well, four decades. The unveiling of the company’s first production of the second opera in Wagner’s Der Ring des Nibelungen, the cycle’s most popular work and a premiere that may surely expand the company’s artistic ambitions, loomed at the end of April. As the weeks passed and anticipation grew, a bombshell announcement further raised the ante exactly one week before Die Walkure’s opening night. Our scheduled Brunhilde, soprano Wendy Bryn Harmer would regrettably bow out from the production due to an unspecified indisposition. Stepping up to the plate as Atlanta’s first Brunhilde would be the spectacular Christine Goerke, one of the world’s reigning Brunhildes.

I was gagged.

Riding high on pre-performance fumes, Waltrauto arrived at the theater early. Eager to immerse myself in the Ring Cycle experience I joined several of the early arrivals for the pre-opera lecture facilitated by local resident heldentenor, Jay Hunter Morris – His candid and impassioned introduction struck the right balance to prepare both new and seasoned audience members for the 5-hour ride that was to come. This is a rare opportunity to hear a special artist so intimately associated with this repertoire actually speak about his experience, both as a stage performer and a fan, so be sure to check out the lecture if time allows. I suspect he will share great insight next year when the company unveils Siegfried, a role that cemented his international career thirteen years ago.

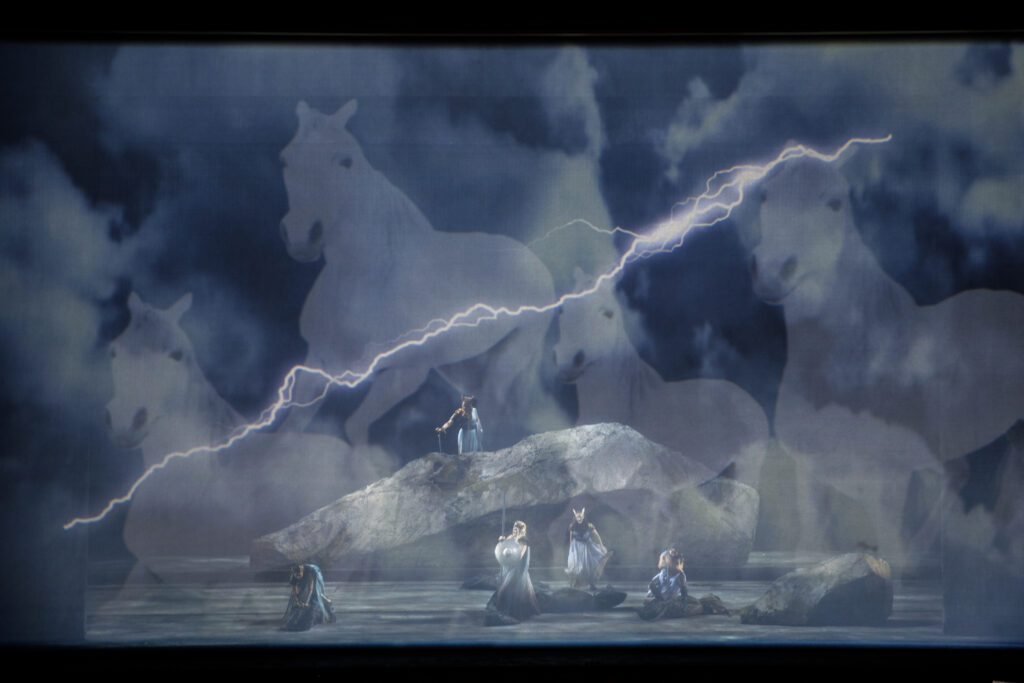

Following the success of last season’s Das Rheingold, when the company met the opera’s technical challenges through a clever interplay of stage lighting, puppetry, projections and pantomime, the success of the production values for Die Walkure was less clear cut. Built in conjunction with the Dallas Opera, Edhard Rom’s minimal stage designs served up an attractive background against which the action freely unfolded. When he applied poetic brushstrokes to his scenery, such as his setting of Brunhilde’s encounter with Siegmund in the second act (the “Todesverkundigung” scene) against an oversized eclipse, his achievement was visually striking without getting in the way of the drama. Similarly, Mattie Ullrich’s costumes graced the proceedings with becoming and functional designs, many of which enhanced the dramatic transformation of the principals, particularly that of Mr. Grimsley’s Wotan who appeared unrecognizable since his swaggering Das Rheingold days.

The same could not be said of the work of the filmed media team of Felipe Barral and Amanda Sachtleben. As in previous productions, Director Zvulun superimposed video projections to underline emotional elements, and this is generally most successful when applied with a subtle touch. The arrival of Spring in Act 1, the transition between scenes in Act 2 featured projected filmed sequences which assisted the senses through light suggestion while the ears did the heavy lifting. When asked to tackle full on Grand Opera style deus ex machina devices on their own, however, this brand of stage wizardry is less impactful, and the decision to illustrate the airborne Valkyries with their respective herd through film polarized the audience. To further aggravate, the wails of off-stage Valkyries were projected into the auditorium through speakers, some of which were ill-prepared to handle the intensity of the battle cry, yielding audible distortion. That such distraction was featured during a scene for which the audience’s attention is essentially guaranteed calls the decision further into question. Heavy reliance on filmed media also detracted from the opera’s final stunt, with the projected magic fire never fully synergizing with the fog machines worthy of gracing the orchestral effect. This is not to diminish the overall achievement of the company’s efforts (in several aspects, Atlanta has already surpassed all expectations and offers a tremendous experience), but to underline choices that kept the performance from realizing its full potential.

In the pit, Maestro Fagen had to contend with his own set of complications. Working with Gotthold Ephraim Lessing’s reduction of the score, maestro Fagen was left a reduced string section, which denied him the proper resources to carry out the composer’s effects in the large Cobb Energy Performing Arts Centre auditorium. Throughout the opening night presentation, maestro Fagen seemed to focus great attention to issues of balance, often defaulting to an overtly cautious tempo which blurried his articulation and denied the orchestra a chance to assert itself in its full splendor. In key musical moments the orchestral impact was savored as a blunt mouthful rather than as the interplay of succulent strands. More concerning, maestro Fagen routinely held back his players to allow the principals onstage ample space to complete their phrasings, halting the orchestral effects to the great detriment of several scenes, most notably in the extended duet between Siegmund and Sieglinde which closes the Act 1. Here, the music should build from gestures of recognition and love to unquenchable, desperate lust. And yet the maestro’s beat afforded the Volsung twins with enough time to find contraceptives (and essential cut the cycle by a half). While the maestro’s courteous manner is often appreciated in his leadership of the standard repertoire, this is less congenial in Wagner’s aesthetic where the orchestra must assert itself as the main priority. A casual poll of members of the violin section, many of whom will surely be treated for tendonitis by the end of this run, will anonymously agree. The score has also been subjected to cuts of varying size, with many devotees noticing the loss of Sieglinde’s “mad scene” at the start of the second scene of Act 2, which was a real shame. These concerns notwithstanding, the maestro gradually shook off these first night jitters and delivered an orderly, tidy reading of the challenging score as the evening progressed. I confess to have already attended the second performance and his baton has regained greater confidence, promising much for the final performances of this historic production.

Returning to the Atlanta Opera after a 30-year absence, soprano Christine Goerke became Atlanta’s first Brunhilde last Saturday evening. Her delivery of the famous “Hojotojo!” served to illustrate the hallmarks of her art. Her soprano is gargantuan in size and blunt in its impact on the listener. She is the possessor of a true dragon lady voice, which threatens to go unruly if left to its own devices, thus requiring her constant negotiation with it through idiosyncratic technical means. Her battle cry smites the auditorium through its stentorian profile and the athleticism with which she accomplishes the upward leaps to the B’s and C’s. The trills, however, are barely indicated and the attack to the lower tessitura is thread bare. Later in Act 3, the display of her lower resources was clear and exuberant, only to be followed by drier patches within her scale – all which had previously been heard in a better light, indicating that the complete voice IS there, but perhaps not completely accessible at all times. Yet, when it is (and it is for the majority of her three-hour performance) she sucks up the oxygen in the theater.

Those who have followed her career know that these compromises have essentially been there since the beginning. Her ascend to Valhalla has not been a smooth one, though her art has ultimately benefitted from its hardships. Atlanta Opera audiences became part of that journey in 1994, when, as Clotilde, Ms. Goerke babysat Martile Rowland’s children in the company’s celebrated production of Bellini’s Norma. Her meteoric rise hit its first peak around the year 2000, when her recording of Gluck’s Iphigenie en Tauride sparked a lot of chatter among opera nerds. She seemed poised to ascend to the classical heroine throne, but the voice refused to play along, ushering a vocal crisis which threatened to derail her position. Remarkably, Ms. Goerke took her vocal fate into her own hands by undergoing a full revamping of her technique and embracing the repertoire she always knew would be her destiny. In 2009, very quietly, she scheduled her first Turandot with Jacksonville Symphony, which I recall was announced rather late, allowing little notice to prepare for the 5-hour drive which I ultimately braved to witness her extraordinary transformation. It was certainly worth the speeding ticket I got on my way back home (must escape Florida as quickly as possible). The demands upon her volcanic resources made by this extreme repertoire have curiously rendered Ms. Goerke’s singing engaging and endearing by way of its very battle scars, and the choices made to keep her art within the boundaries of good taste. The fastidious care with which she balances the disparate elements of her instrument is indicative of her artistic commitment.

If Das Rheingold emphasizes the splendor of the gods, Die Walkure focuses on the rot setting in, which will invariably lead to inescapable decay. Returning as Wotan for these performances of Wagner’s Die Walkure, bass baritone Greer Grimsley embodied this theme through an extraordinary feat of stage deportment. Das Rheingold’s virile Wotan has morphed into a figure of reduced presence, whose shattered confidence has inflicted changes in his physicality: His gait is conscious, his brow weathered and thin, his once proud robes overwhelming his increasing frailty. He is deeply troubled by the unsavory path that his decisions are dragging him through, and though still able to wield his mighty power, Mr. Grimsley’s Wotan is keenly conscious of the additional effort required to assert himself, often wincing his remaining eye as if in constant pain. He is barely recognizable as the god who entered Valhalla a year ago.

Reprising his role alongside Ms. Goerke’s Brunhilde, a partnership broadcast around the world through the Metropolitan Opera’s HD transmission of Wagner’s Ring Cycle in 2019 and now live onstage for Atlantans to enjoy in the flesh, this father and daughter team shared palpable chemistry in their various scenes, most touchingly during the opera’s heart wrenching final scene. Those lucky enough to hear him last year will be reassured that, vocally, Mr. Grimsley remains very much a god. His singing remains imposing as ever, though the beat that accompanies his singing at the fortissimo is becoming more and more pronounced as the pressures of his repertoire continue to make their demands upon his august talents. His method is pristine, and he can still express the passions of his part through vocal means at a level few singers can match today. The voice is imposing, dark and authoritative. He can call upon it at all dynamics, from the thoughtful threadbare piano to a thunderous cry, it can turn a gesture on a whim. The registers remain equalized and dispensing a homogeneous color throughout the range.

Wotan’s unlucky offspring, the Volsung twins Siegmund and Sieglinde, were entrusted to two artists making their company debuts. As Siegmund, tenor Viktor Antipenko revealed a gallant voice, cut from lyric cloth, and yet able to assert itself past the orchestra with little effort. Though his singing is amicable, his legato is spotty, and his presentation reveals much of his performing strategy for the public to hear, marring his efforts by a lack of tension and spontaneity. He must develop the art to hide his art. Until then, scenes calling for the utmost abandon will strike the listener as coldly calculated. This was the case in the scene when Siegmund calls out to his father for the weapon he promised him in his time greater need. Here, Mr. Antipenko paid homage to the great Lauritz Melchior by referencing the great tenor’s stunt from a 1940 performance of Die Walkure in Boston. Later as the duet with Sieglinde, he delivered his Liebeslied flat on his back a la Jeritza. Even here, the manner with which he executed these easter eggs impressed more as fait accompli rather than as a dazzling display of vocal bravado. Once warmed up by the rapturous pages of Act 1, his singing picked up steam as the evening progressed and the ear grew to appreciate his efforts. His style grew progressively endearing to the audience, and his musings over Sieglinde’s fate before his own undoing made his demise the more devastating.

As his sister-wife, Laura Wilde made a promising Atlanta Opera debut through her vibrant, fresh-voiced Sieglinde, A young artist of great promise, Ms. Wilde immersed herself into the assignment with intense focus, projecting her full fledge commitment to Sieglinde’s plight in her every phrase. Her significant vocal prowess came to her aid when her interactions with her newfound sibling yielded, despite their best efforts, a certain disconnect that impeded them from establishing a more believably dangerous affair. Thankfully, her impassioned singing more than made up for the lack of chemistry. Her soprano exhibits qualities associated with the lyrico spinto fach: An incandescent tone wielded with a steady emission throughout an even scale, rising above the orchestra with glowing fervor. These are, of course, the building blocks needed to deliver a Sieglinde worthy of the assignment. She is, after all, the key to the salvation of the world, and as she exited the stage by introducing the all-important “Redemption through love” leitmotif, Ms. Wilde did not disappoint.

The oppressive spouses of Die Walkure were led by the Fricka of mezzo soprano Gretchen Krupp. A former Glynn Studio Artist and last year’s Flosshilde, Ms. Krupp returns to the stage of the Cobb Energy Performing Arts Centre in her biggest assignment yet, fulfilling the promise revealed in previous performances. Filtered through her impersonation as the great goddess of marriage and wife to the great Wotan, the assignment afforded the listener greater opportunity to hear her out, and though terribly excited, I was left with more questions than answers. Her tone is gleaming, clear and naturally projected at the top of her scale, projecting beyond the orchestra like a velvet fist. A less natural, more calculated method is registered as she navigates south towards the lower tessitura, and though her chest voice is responsive, it is hardly featured as the jewel in her vocal arsenal. Modern ears accustomed to dark, carvernous tones from the mezzo clan will find her designation confusing and inspire accusations of “lazy soprano”, that is, until they become familiar with the great mezzos and contraltos from the early 20th century tradition (Sigrid Onegin, Ebe Stignani, Giusepina Zinetti). Only then will they become extremely excited about her possible development. She must continue to work to equalize the chest and middle register to match the natural richness of the top, remain patient, and dismiss all pressure to over darken. Back on earth, of bass Raymond Aceto succeeded in projecting a boorish Hunding though an imposing and wooly textured bass, befitting his character’s profile and sensibilities.

Any attempt to describe Brunhilde’s sisters beyond variations of “loud” would prove exhausting, and ultimately be unfair for the artists. The Valkyries must be loud, imposing, and converge their forces to smite the audience with their famous ride. They’re vital for the success of any Die Walkure and often times the names of future stars will be found among their ranks. And so we these talented ladies who gave the audience the ride of a lifetime last Saturday. They include two returning artists: Glynn Studio Artist Aubrey Odle who undertook Siegrune, and Alexandra Razskazoff as Ortlinde. The remaining Valkyries all made Atlanta Opera debuts in these performances, starting with Julie Adams as Gerhilde, Yelena Dyachek as Helmwige, Maya Lahyani as Grimgerde, Meridian Prall was Schwertleite and Deborah Nansteel as Rossweisse. Out of the pack, the clarion voice of mezzo soprano Catherine Martin shone vividly through the caucophony.

If you missed the first two performances of the Atlanta Opera’s production of Wagner’s Die Walkure, do not fret! There are still two more performances left in this run.

Do not miss your chance to be a part of this historic event!

We have Christine Goerke for two more shows!

We have Greer Grimsley for two more shows!

Two more shows, people! Two – more – shows!

For ticket information, please visit the company’s website at www.atlantaopera.org

-Daniel Vasquez